As riders, we often spend many hours training independently without regular access to high quality coaches, sport psychologists, biomechanic specialists or exercise physiologists. This can be the difference between performing well and performing to the best of your ability consistently and reliably over the long term. Be Your Own Equine Sports Coach covers topics including making sports psychology work for you; understanding human peak performance; the physiological and biomechanical demands of horse sport; developing sport specific training programmes; analysing your performance, and finally, strategic development and authentic leadership.

Analysing Your Performance

Observation is the most common method that we, as riders, use to analyse our competition performance. However, studies have shown that observations are both unreliable and inaccurate. Human memory is limited, and it is almost impossible to remember all the events that took place before, during and after each class. Add in any emotions and how you felt about your performance and you may find that what you thought happened and what actually happened are quite different. In a study of over 650 event riders asked to recall their dressage score in their most recent competition, 20 per cent were unable to recall their score accurately one to five days post competition. This figure increased to 70 per cent if riders were asked to recall their score after more than twenty days, and interestingly riders who had a poor score were less likely to recall it accurately! (Murray et al., 2004).

Even asking your coach or trainer to provide feedback may not be objective enough. Research suggests that experienced coaches are more likely to detect differences between two performances than novice coaches – exactly what you would expect – except that these experienced coaches saw differences even when none existed. They also tended to be very confident in their decisions, even when they were wrong (Hughes and Franks, 1997). I’m not saying don’t listen to feedback from your coach or trainer – just that there is also a place for a more objective and scientific approach to analysing your performance. In essence, human memory and observation are not reliable enough to provide sufficiently accurate information to enable you to improve your performance.

The Purpose of Performance Analysis

The purpose of performance analysis is to examine outcomes (what’s going well, what’s not going well, and what needs changing) and the factors that influence those outcomes. In dressage, an outcome could be the score for each movement, or the overall score for the test. A successful outcome might be a personal best score, a placing, or winning a class. In show jumping, an outcome might be the negotiation of each jump and the factors that influence its successful completion – for example, the turn to the fence or the take-off point. In eventing, an outcome could be the number of penalties incurred during the cross-country phase, a successful outcome being going clear within the time allowed.

One of the most useful tools for analysing performance is the camera. Recordings provide a backup system to support or refute any observations that you made about the competition. It tells you exactly what happened, which may or may not tally with your perception of what happened. You are probably already in the habit of recording your tests/rounds and replaying them at home to relive the experience and gain insight into why you got the result you did, and what could be improved on. However, this recording generally doesn’t give an account of what went on before you went into the arena, and often it is these peripheral things that have the greatest impact on performance:

• What you ate or drank.

• What was said to you by others (coach, family, friends, other competitors).

• What you said to yourself.

• The length, quality and content of your warm-up.

• The general organization and planning of the day.

• What you did (for example, watch other competitors or listen to other people’s advice).

• How you learnt the course.

• When you learnt the course.

It’s very powerful to be able to see for yourself the change in your body language, confidence levels and self-talk when you have, for example, watched other competitors in the same class. It’s quite normal to be unaware of how you are affected by the things you do or say before entering the arena. It is also quite normal to be adamant that you didn’t do, or say, or behave, or react in that way, so visual evidence can be very revealing! For videoing to be effective and to allow you to identify as many influencing factors as possible, ensure that you capture as much as possible – your preparation, warm-up and trot/canter round before the bell, as well as the course or test itself. At its simplest level, performance analysis is about noticing what happened, and asking questions about what influenced what happened. While it is useful to do this on a class-by-class or event-by-event basis, performance analysis really comes into its own when it is used to identify any patterns or recurring themes over a series of competitions.

Subjective measures, such as considering how you felt the round went, can be a useful source of immediate feedback. Take particular note of what you were thinking about or saying to yourself during the warm-up, prior to going into the arena, during the course, and riding out of the arena. The answers can provide an insight into your psychology at these times, and may give clues as to why a particular outcome occurred. However, research has shown that free reports (unstructured discussion) can result in many emotions and thoughts being added or omitted. This is particularly true if there is a time delay, such as discussing the event at your next training session (Tenenbaum et al., 2002). A more structured approach is achieved by writing down or recording your thoughts, observations and feelings after you leave the arena. Do this for each class, and then compare what you wrote with the video of that day and the eventual outcome – successful or otherwise. What did you notice?

Sport-Specific Analysis

A detailed review of dressage tests while reading the judge’s comments will reveal your persistent faults… This forensic analysis can also be applied to show jumping and cross country. ~ Jonathan Chapman, British Eventing Life (November/ December 2018)

Dressage

There’s a commonly held belief among dressage riders that they have little control over the marks they are awarded, mainly because tests are marked subjectively and often by many different judges throughout the season. However, performance analysis can reveal a lot of information about what influences those marks; which qualities particular judges value more highly than others – especially useful at the higher levels where you are likely to encounter the same judges throughout the season; whether judges forgive minor inaccuracies in favour of, for example, high quality transitions; as well as many other factors that may affect your ability to ride the test to the best of your ability.

Test sheets

Test sheets, when taken all together, are a useful source of information on trends. Individual test sheets are an interesting snapshot of the day but are limited in terms of performance analysis because one mark is awarded for a movement that may involve several different actions (changes of direction, turns, circles and transitions). However, analysing a season’s worth of test sheets helps you understand any general patterns in the marks, which may be affecting your overall placings:

• Look at frequently occurring movements in the tests you are riding and calculate the average mark for each over the season. Why not prioritize your training sessions to work on movements that are averaging less than a seven?

• Look at the average scores over the season for each pace. Are all three paces scoring roughly the same mark on average? If not, can you use your training sessions to get them all up to the same level?

• Look at the average of each of the collective marks over the season. What do you notice?

• Look at the judges’ comments over the season’s test sheets. Are there comments that appear frequently? Have you taken on board any suggestions?

• Look at all the test sheets from a particular judge. Are there any recurring themes in the marks or comments?

• Are some paces or movements consistently achieving higher marks than others? Is this consistent over a number of tests or over a season?

• Were the movements performed at the markers, or between the markers as required? Did the accuracy affect the individual marks for the movement, or just the final collectives? In general, is a good but inaccurate transition rewarded more highly than a mediocre but accurate transition?

In addition, you may want to consider:

• Do you always follow the same routine prior to entering the arena? How much time do you spend on average going round the outside of the arena? Does this have any influence on your performance inside the arena? Perhaps experiment with different approaches to the trot/canter round to see which is more effective than others.

• How much time do you take in the warm-up overall? How much time is spent in each pace and on each rein? What movements/transitions are performed? How much time is left between completing the warmup and entering the arena? Is there an optimum warm-up time? What did you do in the warm-up on days that you produced a high- or low-scoring test?

Simple Analysis of Your Test Sheet

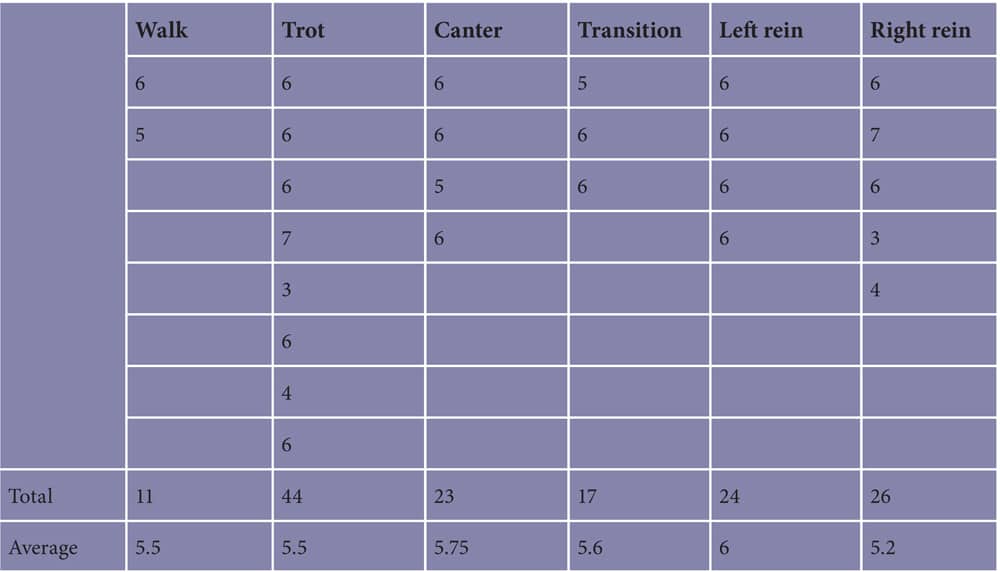

Draw a grid like the one shown in Table 13.1. Take a recent test sheet and list the marks you received for each pace (walk, trot, canter) and each transition. Then go back and write down the marks you received for movements on the left rein and the marks you received for movements on the right rein. Add up the total marks for each column, and then divide by the number of marks to get the average – for example, the total marks awarded for trot movements in the test equalled 44, and the average mark for each trot movement was 5.5 (44 divided by 8).

Note: The collected marks have not been included in this analysis as they tend to reflect the marks awarded for the movements: improve those marks, and the collectives will improve. Equally, don’t worry too much if one of the movements has, for example, a trot-to-canter transition in the mark: I tend to list this under transition, because it’s highly likely that the transition is what the judge will focus on when awarding a mark for the movement.

Table 13.1 Analysis of a dressage sheet.

What do you notice? Interestingly the analysis in Table 13.1 immediately shows that, in this test, more marks are awarded for the trot than the walk or canter, and while the average mark for each pace is roughly the same, if you could increase the average mark for the trot movements the overall mark would be significantly improved. The other area of interest is the difference between the marks on the left rein and those on the right rein. This might indicate a need to spend slightly more time training on the right rein than on the left.

If you did the same analysis for the next ten dressage sheets at this level (in this case Novice) and compared them, you would be able to see if there was a general trend of getting more marks for movements on the left rein than on the right, or for one pace more than the others. You could also do the same for all your test sheets at that level over the course of a season. This would give you a great overview of where you are now, and allow you to chart your progress compared to last season’s marks, as well as provide a benchmark for monitoring your improvement next season.

***

Order your copy of Be Your Own Equine Sports Coach HERE.