Pace and Impulsion

Definitions

In simplest terms, pace equals speed, and impulsion equals thrust. They go hand in hand to a certain degree because as a horse increases its pace, its thrust also increases, both on the flat, as the animal pushes off the ground harder to achieve greater speed, and over fences, when the greater pace allows the horse to launch its body weight more easily. However, there is a point at which a horse needs more impulsion, but not more pace, in order to turn in a first-rate performance—that is, simply going faster will not improve the quality of the round, but having more impulsion will.

For instance, in courses involving tight turns, such as a handy hunter course, a horse cannot create sufficient thrust off the ground at the fences by simply going faster, for the acuteness of the turns restricts the pace. However, a rider can create more impulsion in the horse by adding leg and balancing the horse with the hands so that the horse’s engine—its hindquarters—will push harder while the rider’s hands will restrict the horse from gaining speed. (See chapter 4, “Equitation on the Flat,” and chapter 5, “Equitation over Fences,” for a more detailed discussion of the rider’s control of the horse’s impulsion.)

Pace is related to horizontal motion in the horse, for the horse that is asked to go forward by the rider’s legs and is unrestricted by the rider’s hands will stretch forward into a longer stride, create a faster speed, and move in a flatter frame. In contrast, impulsion is related to vertical motion, for a horse that is asked to go forward by the rider’s legs and is restricted by the rider’s hands will have a more vertical motion to its strides; while the rider’s legs create more energy, the rider’s restricting hands cause that energy to be used in upward, thrusting motion.

The Correct Pace

There is no set speed at which every horse should be going when approaching fences. The pace depends upon many things, such as the size of the fences, the horse’s length of stride, and the way the course is set. The best rule in judging pace is, “Use your common sense.” Does the horse look as though it is going too fast or too slow? Does the round appear dangerous because of excessive speed, or dull because of too little pace? If the answer to any of these questions is “yes,” then the horse’s pace is inappropriate for the course.

The Correct Impulsion

Judging proper impulsion is considerably more difficult than judging proper pace. Basically, we can equate impulsion with the horse’s athletic ability. Does the animal use its hocks well as it takes each stride so that its hindquarters are well under its body? Does the animal rock back onto its hocks when it jumps, or does it simply “jump off its front end,” using as little push power from its hocks as possible? If the horse doesn’t have impulsive, athletic strides and good, solid thrust off the ground at each fence, it doesn’t have enough impulsion. Although impulsion will not be marked separately on the judge’s card, it will come into play when considering “way of going” and will be evident in the markings concerning the horse’s jumping form, which inevitably suffers when the animal lacks sufficient impulsion.

The horse’s vision, balance, and length of stride are compromised when it is not bent in the direction of travel (left). In contrast, when the horse is properly bent, the rider and horse are aligned on the same axis, providing good balance, vision, and continuous momentum on the approach to the upcoming obstacle (centre). Compare the properly bent horse to this animal that is drifting to the outside of the turn (right). Drifting causes the path to the upcoming obstacle to become longer than intended, making it difficult for the rider to find the proper takeoff spot at the fence, and leaves the horse unbalanced at takeoff, with too much weight on one side of its body. (Bill Johnson photos)

Bending

Since much more time is spent going between fences than actually jumping them, the way a horse travels between the obstacles is extremely important and gains more importance as a deciding factor between horses as the competition gets stiffer. To make a horse look its best on course, the rider must keep the animal straight in its body on straight lines and bent in the direction of travel on bending lines (images above).

In a typical hunter course, the horse will be asked to negotiate two straight outside lines, two straight diagonal lines, and five curving lines, which include the beginning and ending circle. Since a large part of every course is performed on curving lines, a chronically unbent animal will not be successful in top-notch competition.

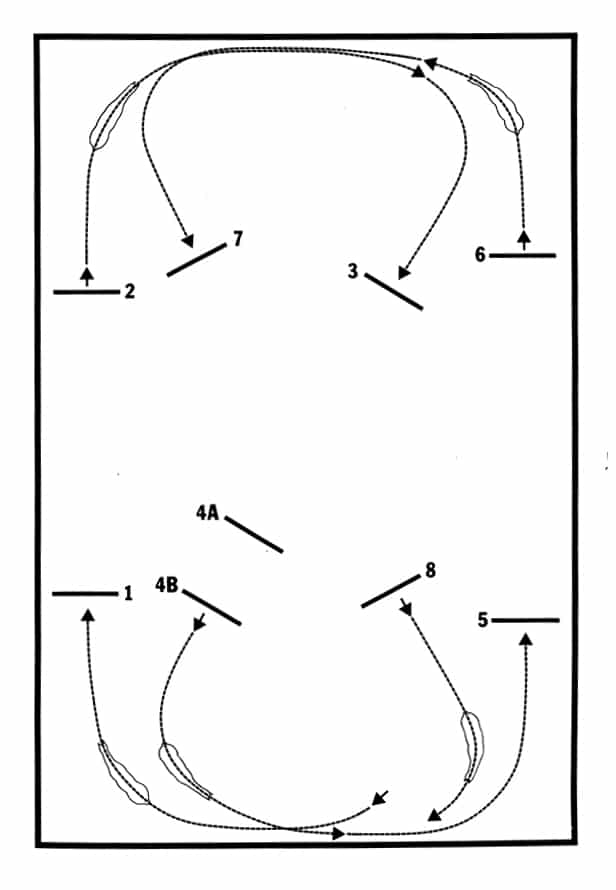

Five bending lines are shown in this diagram of a typical hunter course. Since much of every course is performed on curves, a chronically unbent animal should be heavily penalized.

Balance, Vision, and Impulsion

Besides the fact that the unbent horse produces an unattractive performance, there are a few safety reasons for penalizing the animal. As it negotiates corners with its head cranked to the outside, it carries most of its weight on its inside legs. This means it is traveling off-balance, which can cause serious problems in good footing as well as bad.

When a horse is unbalanced around corners, it has difficulty jumping fences close to them and will sometimes “jump off one leg.” Occasionally, a horse will even run through a fence, because its head is turned so far to the outside that it can’t see the obstacle toward which it is galloping.

Also associated with the unbent horse is the problem of maintaining enough forward momentum to “make the distances” between the fences. A horse that is not bent around a corner will lose impulsion and shorten its stride by leaning toward the inside of the curve—two faults that make it nearly impossible for the horse to travel to the next fence in the correct number of strides.

As for the aesthetics involved in judging the unbent horse, the combination of a short-strided, unbalanced, and stiff animal is hardly a winning one.

Changing Leads

Landing on the Lead and Flying Changes

Many hunter classes are lost by horses that won’t go around corners of the ring on the correct lead. I believe the smartest solution for the rider is to teach his horse to land out of the air onto the correct lead at the end of each line by using the outside leg aid while the horse is airborne—the same aid that is used for the basic canter depart. However, both landing on the proper lead and performing a flying change are correct, and a rider is free to use whichever solution he or she prefers.

Counter Canter vs. Cross Canter

As for the horse that lands on the incorrect lead and refuses to perform a flying change, the animal will take one of four options: stay on the counter canter around the entire corner; switch leads in front but not behind, resulting in a cross canter around the entire corner; cross canter for a few steps before switching completely onto the proper lead; or, cross canter the corner and switch back onto the counter lead on the approach to the upcoming fence.

Although a horse traveling on the counter canter is not properly balanced on corners, it is preferable for a horse to remain on the counter lead than to maintain a cross canter through the entire corner, for the cross canter is disjointed in appearance, affects the rider’s ability to place the horse properly at the upcoming fence, and causes the horse to be unbalanced. Further considering balance at takeoff, it is preferable for a horse to cross canter the corner and switch back onto the counter lead just before the fence than to attempt to jump the fence out of the cross canter.

However, in comparing the horse that cross canters a few steps with the horse that maintains the counter canter around the entire corner, the horse that cross canters and switches would be preferable, for the animal would be on the proper lead for at least part of the time and would be better balanced for takeoff.

In judging the class, then, the horse that landed on the correct lead after each line and the horse that properly performed the flying changes would be considered equal. However, in top competition, the horse that lands on the correct lead might place higher because its round would look smoother without the interruption of the flying changes. Following the first- and second-place pinning of these two horses, the next would be the horse that cross cantered a few steps then switched to the proper lead. In fourth place would be the animal that remained on the counter lead around the entire corner and on the approach to the upcoming fence. Fifth place would go to the horse that cross cantered the corner and switched back to the counter lead on the approach to the fence; and in sixth place would be the horse that cross cantered the entire corner and jumped the fence out of a cross canter.

Breaking Gait

Besides counter cantering or cross cantering the corners, the horse might break gait from a canter into a trot rather than perform a flying change. A break in gait is a serious fault in both classes over fences and on the flat and is worse than a counter canter or cross canter. Breaking gait demonstrates the horse’s unwillingness to go forward from the rider’s leg and is penalized in accordance with other faults related to lack of forward motion. It would only be pinned above severe behavioral faults, such as refusing at a fence or rearing, and other faults that imply danger to the rider, for instance an extremely fast pace or a knockdown (which is considered worse than a break in gait because of the involvement of the horse’s legs with the rails).

Habitual Switching of Leads on Lines

Another error involving leads in the show ring is the switching of leads between fences on a line. This fault normally occurs when a horse is trying to save itself from meeting an overly deep takeoff spot; but it can be the result of an animal’s habit of jumping off only one lead. Whether it is an indication of the rider’s poor placement of the horse at the fence or of the horse’s poor coordination, it should be penalized.

*****

Order your copy of Judging Hunters and Hunter Seat Equitation from Trafalgar Square Books here.