In a global collaboration, we recently published a commentary entitled ‘No More Evasion: Redefining Conflict Behaviour in Human–Horse Interactions’. The underlying goals were to promote positive practices within the equine industry, to safeguard horses against pain, mental stress and unethical training practices and to attempt to generate a consensus among participants in equestrian sports at all levels.

To understand equine behaviour, we must appreciate their telos – how they are hard-wired to act. Horses are prey animals – even today in Nevada, USA, mountain lions are well-recognised as predators of young Mustangs. A female mountain lion was tracked for 10 months and caught at least 20 young horses during that time. Horses therefore have to act before thinking – their reaction time must be quick to try to escape from predators.

They also need to disguise vulnerability, so in the face of musculoskeletal pain they reduce the range of motion of the back, take shorter steps and each limb spends a greater proportion of the stride duration on the ground in order to share load between limbs. These adaptations in gait may help to conceal lameness, but we have become increasingly aware that horses cannot conceal behavioural changes that reflect pain and stress.

Horses are described as grumpy, unwilling, naughty, lazy, anxious, tense, explosive and more – but how often do we stop and ask why?

Riders and trainers often attribute sub-optimal performance to anything other than the horse experiencing discomfort. There is a culture of blame, with horses being described, for example, as uncooperative or explosive, rather than thinking why a horse is behaving as it is. Equestrianism has also had a culture of coercive or punishment-based training, with a lack of understanding of how horses learn.

We hear too often ‘we must make him do it’ or ‘he mustn’t be allowed to get away with it’. Horses are described as grumpy, unwilling, naughty, lazy, anxious, tense, explosive and more. ‘He has a dirty stop’; ‘he jumps well but doesn’t like dressage’; ‘he’s always been a spooky horse – that’s normal for him’ – but how often do we stop and ask why?

The misuse of terminology may mean that signs of stress, fear, confusion or pain are missed. The horse’s motivation for the behaviours displayed may be unrecognised. It deflects blame away from the rider. It often reflects our lack of understanding of how horses learn and how their behaviour is easily altered by confusion, fear and/or pain.

We must understand that a horse’s perception of its environment is different to that of a human being. They have differences in smell, vision, hearing, touch and taste. Their sense of smell is much stronger than most human beings. Horses may see things that are outside our visual field. They may hear ultrasonic sounds that we cannot hear. So, a horse may react to an external stimulus that a rider is not aware of. The horse should not be punished for this unexpected reaction. A horse’s sense of touch is finally tuned so that on feeling a single fly, based on a skin reflex, they can twitch the skin to remove the fly. It therefore follows that we should be able to train horses to respond to light leg cues.

Anthropocentrism also comes into play – the belief that the world revolves around people and experiences are interpreted through our values.

In addition, horses have a major difference in brain structure and function compared with humans. We plan, reason and judge, make risk assessments and decisions. All of this takes place in the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain which is poorly developed in the horse – they need to instinctively run without premeditation.

There is a huge tendency to attribute human characteristics to horses – to anthropomorphise – so for example we describe horses as evasive, stubborn or resistant. However, these terms imply intentionality. Anthropocentrism also comes into play – the belief that the world revolves around people and experiences are interpreted through our values. There is no doubt that horses are sentient beings, but we can only imagine how they feel.

If we look at definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary, we find that to evade means ‘to escape or avoid (someone or something), especially by guile or trickery’. Resistance is the ‘dislike of or opposition to a plan, an idea; a refusal to obey’. Disobedience is a ‘refusal to obey’. These definitions imply malevolent and calculated premeditated behaviour on the part of the horse, which horses do not have the capacity to do.

So, we should ask why is the horse in Figure 1 apparently reluctant to go forwards? What is the motivation driving this behaviour?

Figure 1: Horse reluctant to go forwards; tail swishing, head tilt, mouth open with separation of the teeth and head above vertical. (Compare with Figure 4)

The definitions of disobedience, evasion and resistance in the FEI Dressage Handbook Guidelines for Judges create complete confusion. Disobedience is the ‘wilful determination to avoid doing what is asked or the determination to do what is not asked’. Evasion is ‘avoidance of the difficulty or correctness or purpose of a movement, or the influence of the rider, often with active resistance or disobedience’, giving as an example tilting of the head to avoid correct bit contact (Figure 2). But this doesn’t ask WHY is a horse ‘avoiding correct contact with the bit’. There is a myriad of reasons, for example overuse of the curb rein, backwards movements of a rider’s hands, excessive pressure from a noseband or other causes of pain. Finally, the FEI define resistance as ‘physical opposition by the horse against the rider – which is not synonymous with disobedience nor with evasion’. Clear as mud!

Figure 2: Head tilt, with nose to the left. Was this caused by an attempt to avoid correct bit contact? When pain causing hindlimb lameness was removed by nerve blocks the head tilt disappeared. Note also the intense stare, dilation of the nostrils and the tightness of the flash noseband.

All these definitions fail to identify the motivating influence behind a horse’s behaviour – why does a horse not respond to a cue? Is this because of simultaneous application of opposing cues, for example cues to signal stop and go? Or is the timing of the cues inappropriate? Or is there physical difficulty in performing a movement or underlying pain?

The International Society for Equitation Science, under the initial leadership of Andrew McLean and Paul McGreevy, previously defined conflict behaviour, with respect to ridden horses, as ‘a behaviour caused by application of simultaneous opposing signals such that a horse is unable to offer any learned response sufficiently and is forced to endure discomfort from relentless rein and leg pressures’.

We now know that this is far too simplistic. There are many variable factors that can cause similar behaviours in ridden horses, and it is only by putting the behaviours into context and thinking about the potential causes that we can begin to tease out the motivation for the behaviours.

To understand this better we must comprehend how horses learn. It is straightforward and there are two principal ways. We apply pressure – a leg cue or an alteration in rein tension – the horse responds as desired – we remove the pressure. To be successful the cue must be clear, the rider must pay attention to the response given and the timing of removal of the cue is critical. Alternatively, or in addition, we can positively reward the horse by a sound, a stroke, a treat – again timing is important. For the best results the horse must be in an appropriate state of arousal (state of mind), and the rider must be attentive, responsive and developing the horse’s trust. There is a fine line between adequate arousal for learning and higher arousal that causes stress and inhibits learning.

Fear or punishment create stress and a horse cannot learn. Punishment may be inadvertent – mistiming of leg and hand cues or getting ‘left behind’. Alternatively, it may be deliberate – we’ve all done it – frustration or anger being taken out on a horse. Punishment, for example hitting a horse after it has stopped at a jump, can create both fear and confusion. Coercion may create short-term compliance, but for longer-term harmonious results there must be a relationship of trust and understanding between horse and rider.

It is also important to recognise that horses can experience one-trial learning. For example, fear or pain may trigger a horse to rear. The rearing may be rewarded by the rider releasing rein tension. Rearing may then become habitual and may be confounded by a rider’s apprehension of the behaviour. Horses are quick to learn, but slow to unlearn.

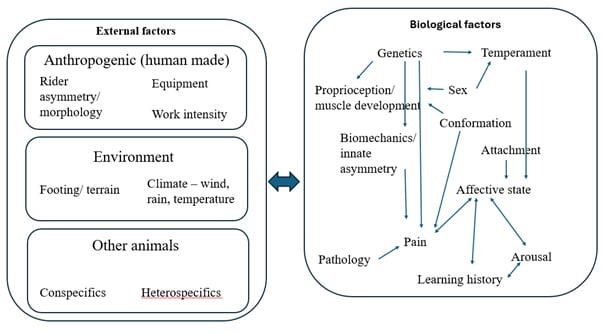

On a day-to-day basis there are many factors that may motivate a horse’s ridden (or driven) behaviour: the weather, the footing, rider asymmetry and balance, work intensity, the presence or absence of other horses, pain, learning history and many more (Figure 3). Moreover horses are individuals and there is not a ‘one size fits all’ recipe for training.

Figure 3: A summary of some of the factors that may motivate a horse’s ridden behaviour and how they may interact.

For this reason, we have proposed that conflict behaviour should be redefined in the context of horse-human interaction (especially riding) as:

- Responses reflective of competing motivations for the horse that may exist on a continuum from subtle to overt, with frequencies that range from a singular momentary behavioural response to repetitive displays when motivational conflict is prolonged.

The redefinition of conflict behaviour offered here encompasses the frequent complexity of conflicting motivations for horses when interacting with humans. In the face of growing concern for equestrianism’s social license to operate and advances in technology that may characterise horses that are fit for purpose in various pursuits, the need for clarity in reporting and understanding problematic behaviour is pressing.

The new definition recognises that pain can be an inciting factor of conflict behaviours. This is good news for horses and good for creating more unanimity in the equine science community. The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram (RHpE) (also known as the Ridden Horse Performance Checklist) is a tool developed to facilitate the recognition of pain. It can help to differentiate horses which are experiencing pain from those demonstrating similar conflict behaviours for other reasons. Conflicting cues in the absence of pain will not result in a RHpE score of ≥8/24 (the threshold score indicating the presence of pain). Moreover, those behaviours which are pain-induced are generally not habitual; when pain is removed the conflict behaviours rapidly resolve (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The same horse as in Figure 1 immediately after removal of pain using nerve blocks.

In essence, to strive towards harmonious horsemanship we need to observe and listen to horses carefully and try to engender their trust to create the best learning environment. A horse must feel in a place of safety to learn optimally. We need to banish terms such as evasion from the equestrian vocabulary and embrace the term conflict behaviour and try to tease out the underlying causes. We will all make mistakes in riding and training. We need to learn from those mistakes.

We encourage everyone in the equestrian community to become more aware of conflict behaviours and dispel the myths of grumpy and lazy horses. We need to be vigilant to recognise the onset of unwanted behaviours and to be constantly asking ‘why?’ and ‘what are we going to do about it?’

The Latest