Tim Worden is an Equestrian Sports Science Consultant based in Milton, ON, specializing in biomechanics, from the University of Guelph. Worden, a member of the board of directors of the Sport Horse Research Foundation, has worked with top FEI riders using analytics and evidence-based training to improve performance. He spoke at the Exercise Physiology Florida 2024 conference about matching the level of training or competition an athlete is pursuing with their actual fitness level – whether horse or rider.

Worden began with the difficult balancing act coaches of both humans and horses face. “We need to challenge athletes to allow them to adapt and grow, but on the flip side, you need to make sure that you don’t stress them too much. You don’t want the athlete getting injured. You don’t want to influence or ruin their confidence, but if you don’t push them enough, then they’re not going to grow and reach their full potential.”

He pitched a simple hypothetical experiment involving three hurdles a foot off the ground and asked audience members how they would get from point A to point B as quickly as possible. “There are two routes to take: you can either step over the hurdles to get from start to finish, or you have to go around, which will take more time.” Of course, most audience members indicated they would take the fastest route over the hurdles.

Next, the imaginary hurdles were raised to belly button height. A few ambitious people said they would try to jump them, but the majority opted to go around, effectively failing the experiment. “In reality, most people are going to take the easier option. At that point, we’re always weighing what is possible and what our bodies are capable of doing, versus what we can do safely.”

So why do some people ‒ and horses ‒ view a task as possible, while others view it as impossible?

“There’s a lot of research out there, both in humans and in animal models. We’re actually quite good at perceiving what our bodies are capable of, but it changes from day to day; just because you’re capable of doing something today doesn’t mean you’re capable of doing it tomorrow. If you are on a ‘winning streak’ you’re feeling confident and you’ll be more likely to to view a task or an action as possible. But if you are fatigued, if you’re in the dumps right now, you’re less likely to view that as possible.”

This is also something that is seen in the equestrian world. “If you see horses in a jumper ring stopping, horses that are really resisting doing certain dressage movements, for example, you always have to wonder, is it because they’re being naughty, or is it because they perceive that what we’re asking of them is not possible? To refuse a jump actually takes quite a bit of energy, and they probably know they’re going to get a correction, so in that horse’s mind, they’re making a pretty drastic decision to take the ‘out’ versus actually jumping and getting to the other side.”

Comparing an equine athlete to its peers

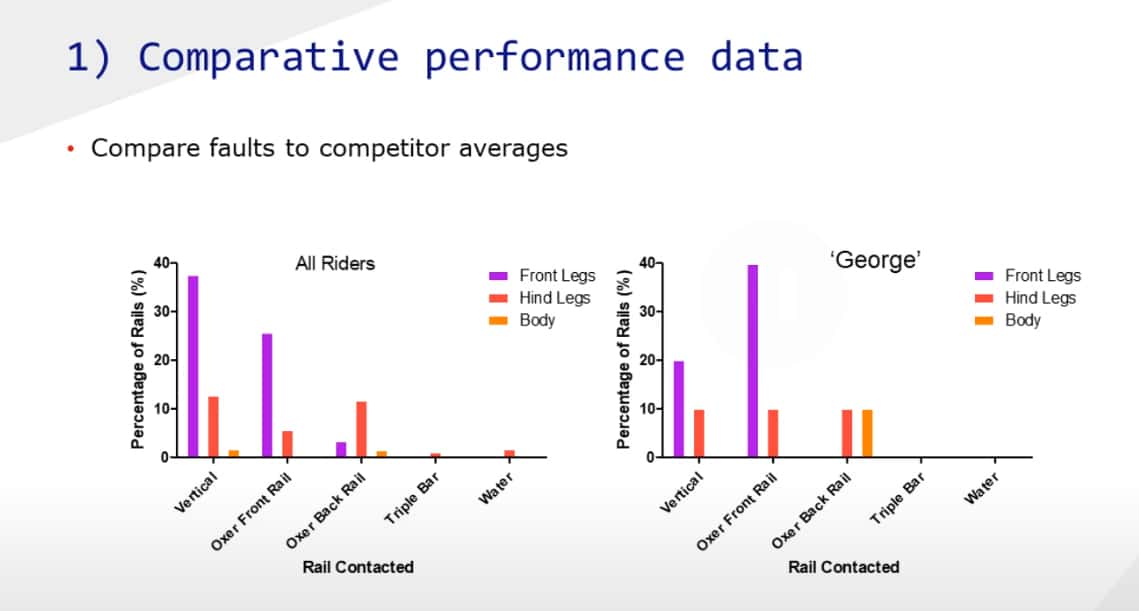

Years ago, Worden collected data from FEI jumping horses with the help of a team that coded in thousands of rails in the competition ring. “You end up with what an average FEI horse does in the ring; you see the percentage of rails that are verticals, oxers, oxer front rail, back rail, and whether it’s front limbs or hind limbs having those rails. And then you can compare your individual horse to that data.”

He compared performance data (below) with a horse he called “George.” “This hypothetical horse, George, is much better at verticals than the average FEI horse, but he’s much more likely to knock out the front rail of an oxer. So pretty quickly, you know that this horse probably struggles getting across the width of those spread fences, and is more likely to have a flatter takeoff trajectory to ensure they get across the jump. That allows you to adjust things in training to match what that horse’s limitations or deficiencies are.”

He singled out an audience member, Canadian Sean Jobin, who is based in Ontario and Florida. Jobin won the Canadian Show Jumping Championship riding Coquelicot vh Heuvelland Z (‘Licot’) at the Royal Horse Show in 2023.

“I think a rider that does this very well is Sean Jobin. He has been tracking data on his horse, Licot, for years. He and his staff know that horse incredibly well. They pay attention, and ultimately, ended up with a national championship.”

Analyzing movement

Whether horse or human, preparing for competition involves upgrading the nervous system, the cardiovascular system, muscle, bones, tendons, ligaments, fascia ‒ but there are also smaller, more subtle changes that must take place.

Worden designed a tool for diagnosing and analyzing movement errors through video. For example, during takeoff “you can look at structural faults in the horse’s and rider’s position. Are the body positions in the right spot? Are they hitting the key positions that will allow them to generate the force needed to get up and over the jump? Is it issues with velocity, or how much the horse’s body is rotating in the air? Most jumping horses usually have two or three things they really are deficient in. They usually have strengths as well, so train to the strengths and address those weaknesses.”

Worden suggested that another good way to understand where athletes ‒ whether horses or riders ‒ are in their training is to begin adjusting the different constraints within the training. For example, “There are a lot of horses that look amazing in certain situations ‒ but you make small tweaks to the tack, distances between jumps, play around with the speed, and the technique can really fall apart quickly.”

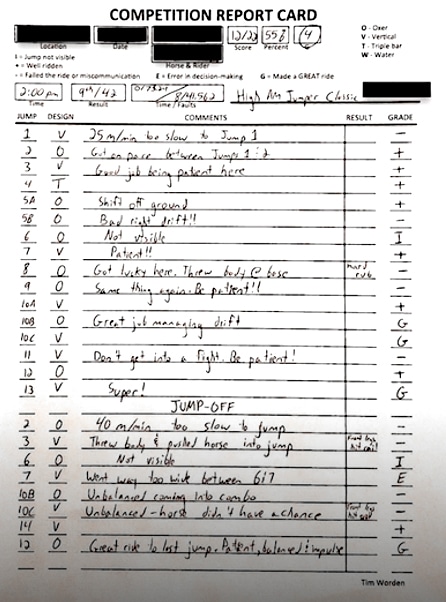

A fence-by-fence competition report card.

Speed can also be very telling. “If horses look really good at a certain canter pace and you ask them to open up or to collect a little bit more, if they maintain their balance, then they’re probably pretty fit and may be ready to do a little bit more. If they don’t maintain that balance, then you may need to take a step back and address some of those points.”

Horses can be rattled by a new setting, and human athletes are no different. “There’s a lot of research on humans that shows that if you put them in different environments, it can have a drastic effect on how well they perform, especially more novice and intermediate individuals. What makes a professional so good is that they can go almost anywhere and still perform at a high level.”

This includes the affect of different surfaces and footings. “If you have a horse that can move pretty well on a bunch of different surfaces versus a horse that needs a certain firmness in the footing to really move or jump well, then that may be something you want to address.”

Daily management checklist

- Stiffness of movement: Is it due to pain, or just uncertainty due to the early stages of training, much like the awkwardness of a human athlete learning a complex new skill?

- Answering the question vs. using cautious strategy: An example is young jumping horses who clear the fences by a mile because they don’t really know where their body is relative to the jump (proprioception). As they learn more, they can read the jump better and don’t need to clear it by as much, because they’re more precise with their trajectory and how they fold their legs up.

- Varying speeds: If the horse can maintain its balance when asked to open up or collect, it may be ready to step up.

- Take video and keep a fence-by-fence ‘Report Card’ of your horse’s rounds to better identify what they do well, and what they are struggling with.

Take-home message for coaches/trainers

“Really pay attention to those day-to-day changes in your athletes, and keep data on that,” suggests Worden. “If you have a horse or a rider that are really resisting doing something today that they were doing quite happily a week or two ago, you have to ask, is it them having a bit of a difficult day, or is there something underlying that is maybe not right in the body? They’re too tired, they are a bit sore or whatever.

“Finally, look for objective ways to monitor how the horse and/or rider are responding to training, for example, making notes about how easy something looks, and asking your horse to do things in a bit of a different way to see how well it can adjust.”

The Latest