We must recognize that most problems—and often the biggest ones—in horse-human partnerships develop due to a failure to listen well enough and to misunderstandings.

Therefore, reading a horse’s behavior should be the priority as you educate yourself. Reading means observing with all your senses, taking in all signals without judgment, and being open to the animal’s answers. Reading means understanding the expressive behavior of the whole horse without judging his behaviors or anthropomorphizing them. Good reading is not defined by speed, but by thoroughness. Anyone can learn to be fully present with a horse carefully and mindfully.

Imagine sitting in a café and watching the people passing by. With a little distance, it’s easy to observe them and notice their peculiarities—easier than with the person sitting with you at the table, and much easier than with yourself. The advanced study of “reading horses” is a very intensive course that requires a lot of homework, which includes observing him not only when he’s interacting with you but also when he isn’t.

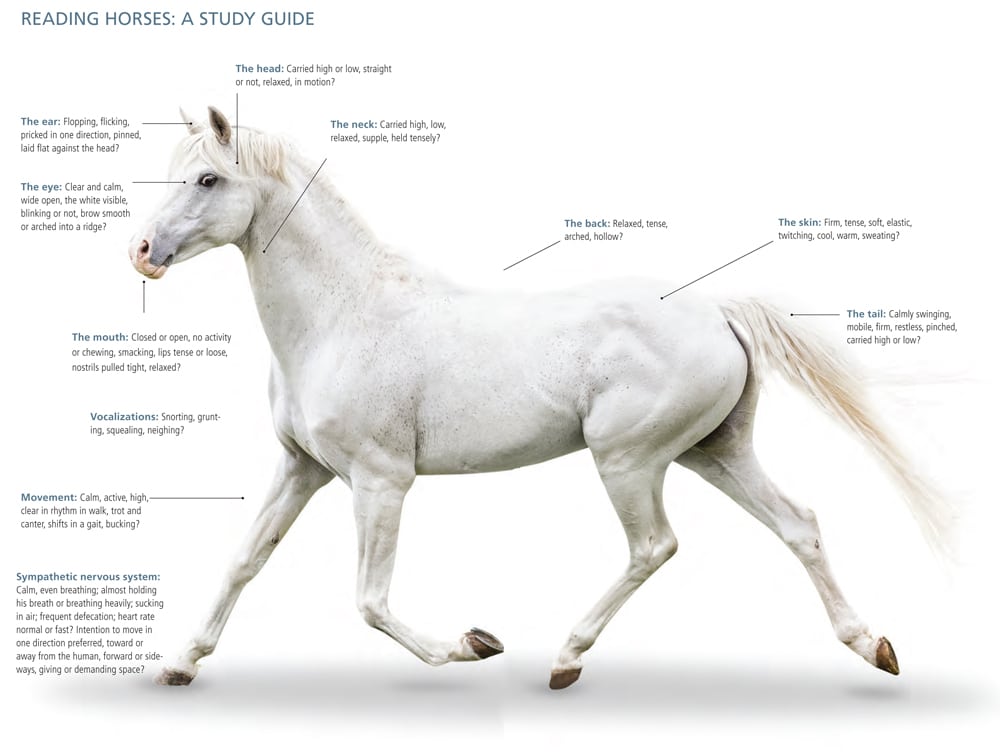

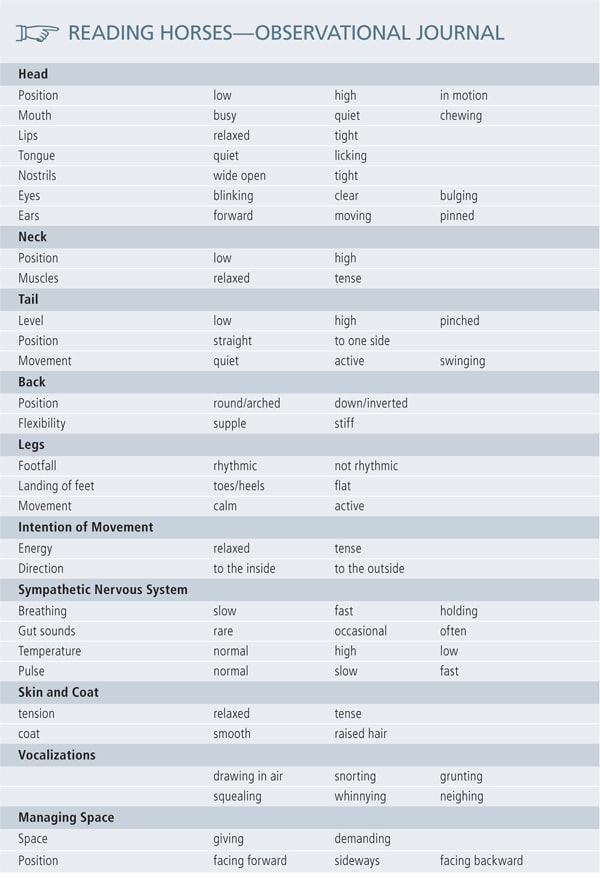

READING HORSES

Sit with your horse in the paddock, in the pasture, and in the stable. Now watch. You are also welcome to keep a journal (see below).

While you study your horse in his free time, start at the front of his face, at the muzzle. How does his mouth move when he moves? What do his lips, tongue, and nostrils do? Watch him when he’s eating, and when he isn’t. Study his eyes: How often does he blink? How do his eyes look? What are his brows doing? Are they arched, pinched, or smooth and flat? How is the bulge above the eye (the soft tissue over the ocular ridge) shaped? Watch his ears: How mobile are they? Are they free of tension, actively listening, or passively resting? Is one ear doing something different from the other? How does your horse hold his head? Straight, at an angle, up, or down? What does his neck do? Is it relaxed, dropped, tight, raised, or lowered?

Look at his topline: is it relaxed, flexible, arched up, inverted, crooked, or loose? And his tail—is it mobile, active, tense, relaxed, pinched in, or perhaps even crooked or stretched? Do his legs move with relaxation and in rhythm in each gait, or are they stiff, tense, or out of rhythm? How are his hooves landing? Do they land flat on the ground or toe first? Observe his breathing, body temperature, muscle tension, and heart rate. Observe him with all your senses. Listen to whether he is holding his breath or breathing normally. Is he snorting, chewing, or grinding his teeth? Is he smacking his lips or rolling his tongue?

Look closely. Even closer! Film him with a slow-motion app and study what you see. Observe your horse without trying to interpret what he’s doing. Keep a record and curb the impulse to put your own words in your horse’s mouth.

Reading the horse means perceiving him from front to back, to recognize how he moves, how he uses space and time. It means being open to the horse’s responses so as not to impose your own perceptions on him. This is the first and most important step in establishing a dialog based on trust.

We read the horse without judging it. The important points can be found in this overview. All these signals result in the expressive behavior of the horse. A single individual signal is not meaningful, only the totality of everything we perceive allows us to draw conclusions about the horse as a whole.

OBSERVING WITH EVERY SENSE

OBSERVING WITH EVERY SENSE

Maybe you’ll catch yourself describing what you think the horse wants to say? If so, you didn’t read so much as interpret: you actually revealed something about yourself, about what you think and what you want, instead of about your horse. A “true reading” only describes what is literally present, without embellishment or interpretation, objectively and factually.

HEARING WHAT ISN’T SAID

In interpersonal relationships, you know what to expect in a dialogue, what should be there and what shouldn’t. Sometimes, we only notice later, when the situation is over, that something was missing. We remember, and then ask ourselves: Gosh, did he actually say “thank you”? Did he say hello to everyone here? Maybe there was a smile missing, or a nod that wasn’t given. Hearing what isn’t said—learning to pay attention to which signals are missing just as much as which signals are given—is a crucial aspect of learning to read horses.

READING WHAT ISN’T VISIBLE

If you observe your horse in his free time, you will notice how often he opens and closes his eyes. You will notice what his breathing is usually like and what he does with his tail. If you want to ride the same horse and stand next to him in the arena, then observe as you mount how frequently he blinks, what his breathing is like, and what his tail is doing. Do not think that everything is fine just because your horse is standing still. A horse standing still without blinking can be a ticking time bomb. If a horse is tense enough that he doesn’t feel comfortable blinking, that could become a problem very fast. Recognize what is missing, not just what is there.

Did you know that horses greet people by blinking their eyes? It is sublime, quiet, and—once you have learned to recognize it—very touching. Horses greet other horses that walk past them with their bodies turned toward each other, gentle angles, softly raised ears, calm breathing, and—the most beautiful thing—blinking eyes.

Like a feather-light touch, they blink at each other and give each other their attention. Personally, I take it as a compliment when they make this gesture when I walk past them. And honestly, I’ve gotten into the habit of blinking back.

It’s also important to notice what isn’t there when you’re riding. Riding as a physical dialogue means that I study the movement patterns and movement intentions of a horse both while he’s in a relaxed state, in a safe environment, and while he’s in tension and under physical and mental stress. Reading in these situations means more than just feeling or sensing while you’re on the ground. When you feel or sense, do not think about your own feelings or about the things your horse might trigger in you.

Rather, just try to describe what you see. One example might look like this:

Independent forward movement; relaxed soft neck, relaxed active ears; longitudinal suppleness, swinging back and tail; relaxed muscles, even breathing, and tension-free skin. Relaxed, rhythmic movement.

This is the description of a typical worry- free horse, but we all know things will not always look this way. In the saddle, just as on the ground, we experience changes first with tension, and second spatially. Telling when the horse’s look has changed, when his back has gotten tight or his muscles are tense, and so on, is similar under saddle and in-hand, but under saddle it’s more direct.

LEARNING A FOREIGN LANGUAGE

Reading horses is a fantastic pastime. It’s like learning a foreign language, although it‘s more primal—simple and direct. Rather than learning grammar and vocabulary, you’re associating a “statement” directly with its behavioral origin. It’s about space, dominance, affection, and security. It’s about survival principles and clear boundaries. It’s not about the type of emotion we cultivate, and it is not about the emotions the horse’s behavior triggers in us, either. A horse always communicates clearly. He expresses an opinion and describes his current emotional state without worrying about potential consequences. A horse is always focused in the present, and communicates with body language and vocalizations. He speaks only one language, and is admirably honest about it.

***

Order your copy of 25 Ways to Make Your Horse Happy from from Trafalgar Square Books here.

The Latest

OBSERVING WITH EVERY SENSE

OBSERVING WITH EVERY SENSE