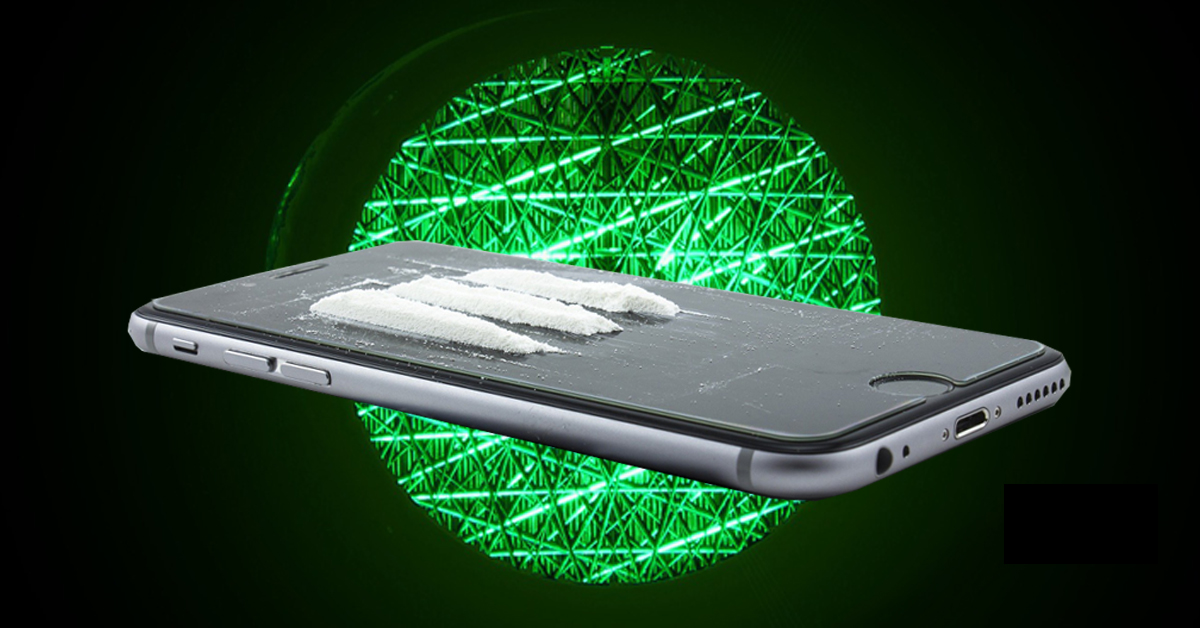

Recreational drug use has become the “main” human concern to the FEI’s anti-doping department. Sampling (in normal times) of riders is still small compared to horses, but when riders do test positive, the substances are often social drugs ‒ cocaine and amphetamines, which are classed as stimulants on the FEI prohibited list, and cannabis.

This topic has been well aired since 2018 at both the FEI sports forum and FEI General Assembly, which revealed that a working group had already been set up, although we didn’t hear much more.

Maybe it was reluctantly deemed a waste of time. From January 1, 2021 the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is obligating all WADA Code signatories including the FEI to show leniency where social drug use is proved to be exactly that ‒ social. When use is “out-of-competition” and not intended to enhance performance, the standard four-year suspension will reduce to a mere three months ‒ just one month if the athlete attends an approved rehab program.

The FEI has flexibility over equine anti-doping rules because FEI is the horse expert, and WADA isn’t much interested in four-legged athletes. But it isn’t allowed to even tweak WADA’s human athlete rules.

The FEI isn’t comfortable about this change. It told me: “During consultation we formally expressed our concerns [to WADA] on the proposed reduced sanctions. As equestrian is a risk sport, we also need to consider the safety perspective. We expressed the view that, in our opinion, the revised sanction was too low and could minimise the deterrent effect.” But, alas, the FEI is manacled to WADA for as long as equestrianism wants to be an Olympic sport.

A four-year suspension will still apply for deliberate cheating. I can’t help feeling, though, that some riders will embrace the change as the green light to party throughout an international show. The likelihood of being selected for sampling is already low. There’s the real possibility that if folk deliberately use stimulants to give themselves an edge while riding, they can now hide behind the “social-use” excuse. From 2021, even if you are caught, the short suspension maybe doesn’t seem so terrible. It might even fall during the “closed season” or at the time you normally give your horses a month off.

I suspect the FEI is more worried about this than it has divulged.

Why is WADA relaxing its stance? Last year during its periodical review WADA was asked to reconsider out-of-competition use. WADA told me: “While the Code does not prohibit the use of these drugs out of competition, sometimes a presence is detected at an in-competition test even though the use occurred in a social context and with no effect on sport performance.

“Where an athlete has a drug problem and is not seeking or benefiting from performance enhancement, the priority should be on the athlete’s health rather than imposing a lengthy sporting sanction.”

WADA added it would be better to spend time and money chasing the real cheats. It has a mountain to climb in that regard, of course, with the growing sophistication of sports doping and involvement of big pharma.

WADA’s definition of “out-of-competition” plays right into typical equestrian time-tabling. WADA defines an “event” as a series of individual competitions conducted together under one ruling body (e.g., the Olympic Games or Pan American Games), and “competition” as a single race, match, game or a singular sports contest. “In-competition” means 12 hours before the start of competition through the end of sample collection. It’s easy to see, then, that if you are riding in mid-afternoon or evening classes, you can easily use party drugs every night and still comply with WADA’s parameters.

Would a rider who wants to feel sharper before jumping a big track fall back on chemical enhancement? I asked several sports psychologists about this. It’s such a touchy subject that two declined to speak to me at all, even to provide off-the-record background.

One that did respond was concerned about unintended consequences of social drugs, such as behavioural changes lasting for some days. Are the stresses of competition driving people to recreational drug use as an escape? Is there covert drug use to embolden the riders who are not ultra brave or committed to their sport, but who are riding at FEI level through peer pressure or ambitious parents?

Another sports psychologist mentioned Adderall, whose ingredients often pop up in FEI doping violations. Adderall is legally prescribed for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD.) It heightens cognitive attention, without cocaine’s negative effects, and because it’s freely available from online suppliers it’s become a popular party drug. Adderall is also commonly used in high finance to heighten and sustain performance ‒ probably, added the psychologist, by the same people who take cocaine in the evening, but for different reasons!

I also doubt WADA devoted much time to considering whether the risk element in eventing was sufficient to block any change to the anti-doping rules of higher profile Olympic sports.

The rise in recreational drug positives also poses wider questions about how seriously some riders take themselves as athletes. For most of us, riding remains a lifelong non-competitive hobby, even when we get quite good at it. Lots of people love the process of training horses for its own sake, without showing. You’d like to think that riders competing in FEI aspire to win, or be placed sometimes at least, and not just spend year after year plugging round the circuit as a mere “get-rounder.”

Less demanding sport categories have been introduced by the FEI to attract the riders for whom national shows used to be more than adequate. However, international equestrian competition has been widely promoted as a lifestyle in the past 20 years, and a huge economy has built up around this. The on-site party scene is a big facet.

Earlier this summer, a German rider who admitted taking cocaine and amphetamines “before 1 a.m.” during a major show saw his likely four-year suspension reduced to two years under current rules. It was accepted that this was an out-of-competition usage, and he hadn’t meant to enhance his performance the next day when the “high” was “long gone.”

Some of his arguments to the FEI Tribunal illustrate how casual attitudes have become among riders who, I assume, want owners and sponsors to regard them as serious sportsmen.

He said that “as result of the good and euphoric atmosphere he let himself be seduced to this irresponsible act and took the drugs.” It was “scientifically proven” that cocaine is only effective for two to three hours. The effect of amphetamine starts after 30 minutes and lasts up to four hours. After this time, even if it still can be traced in the body, for him “there is no longer any effect.” This was his birthday party, in a tent next to the VIP area at the 2019 German national championships, but it was “not official or public” and for “invited guests” only (so that’s alright then – phew!)

Recreational drug positives cost Canada and Qatar their Olympic team jumping places. Those cases are still under judgement, although it seems these riders will offer a “no fault, no negligence” defence because the prohibited substances ‒ cocaine and cannabis respectively ‒ were consumed unwittingly and provided by third parties. Nonetheless, the alleged exposure of these riders to consumption of banned drugs while socialising during an Olympic qualifying event says a lot about the lax education and supervision of riders by their team managers and national federations.

The draft rules are here and the FEI summarises the key changes here.